My journey through the late sixties was hardly a solo trip (but I didn’t know it then). I graduated from the University of Southern California in ’67 after completing my junior and senior years there. My life during those two years was a social blur—I’d joined the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity while a student at LA State and made friends in the USC chapter. Attending football games in the LA Coliseum was a blast, particularly entertaining national TV audiences with clever card stunts performed in the student section during half time. One dark Saturday, November 26, 1966, #1 Notre Dame went to Los Angeles to hand #10 USC a 51-0 shutout loss—the most points scored against USC up to that time and its largest margin of defeat to this day. Meanwhile…

The Vietnam conflict was in full swing, and MLK’s speech imploring the US to to take radical steps to halt the war through nonviolent means had little impact on the Johnson administration. And there I was with a degree in history and little to show for it.

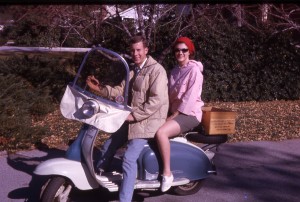

Throughout my 4 years of college, I worked 20 hours a week in the admissions office at Los Angeles State College in suburban Alhambra, even while attending USC in downtown LA. Every weekday evening and Saturdays from 8 a.m. to 1:00, I commuted 45 minutes one-way from my parents home in La Cañada on my cool ’59 Lambretta scooter. Those Saturday mornings were tough, especially in the winter. The Admissions office closed at 4:30 and I staffed an after-hours information window, not unlike a theater ticket office, where evening students had a human interface for all things relating to admissions and registration. It was an exposed, windy area and I recall having to cover my 2’ x 3’ window’s small opening to prevent gusts from blowing papers and whatever all over the place in my cozy “office.” KPFK, LA’s premiere jazz station, was my constant companion, and visitors assured me how wonderful it was to have a compassionate person there to attend to their needs. Most were teachers, chipping away towards a masters degrees after a long day at work. What’s more, male students taking at least 12 credit hours per semester needed me to affix the college’s official seal certifying compliance on their DD 214, the all-important student deferment form required by draft boards. The threat of induction into the military was a dark cloud hovering above all young men during this era, and required careful scrutiny so you didn’t screw up.

My strategy was to follow my father’s lead and pursue a career in education. It didn’t hurt that males enrolled in a course of study leading to an elementary credential were deferred as long as they completed at least 12 credit hours each term. All paperwork was regularly submitted to the draft board for approval (my board was in North Hollywood and had a reputation for being particularly stingy in awarding deferments).

As it turned out, I only needed a single major class in my senior year to obtain a history degree at USC, so I enrolled concurrently at LA State (my employer and where I’d taken my first 2 years of undergraduate classes) to begin my education coursework. At graduation, I’d completed ALL the elementary education requirements generally taken by graduates during the “fifth year” mandated by the state for credential applicants. For most, those 30 credits generally included the core education courses, the “methods” classes on how to teach reading, math, etc., and applying it all during two assignments of student teaching. Since I’d completed all those courses as an undergrad, my challenge was to enroll in SOMETHING for a year, get deferred doin’ it, and begin teaching in the fall of ’69. Enter the brother of a fraternity pal who worked at LA State in the international students abroad office. Over coffee one day, he mentioned there was still space available in a year-long program at the University of Uppsala in Sweden and that I should apply for it. Participants in the program came from all over California, and I happily joined my new friends in Sweden for the 1968-69 academic year, completing my obligatory 30 semester credits required for my teaching credential along the way. As far as my draft board was concerned, I was still in school and working toward my credential.

Fast forward a year later: August, 1969. I’d returned from my year abroad, had received my credential, was hired as a 4th grade teacher at Breed Street elementary school in what was predominately Spanish-speaking East Los Angeles, and was handed the key to room 20 by my principal, Mildred Matthews. I entered what would be my classroom for the next 5 years and took stock of the furniture and teaching materials left for me by the room’s former occupant. The obligatory oak desk, book shelves, a shiny pull-down movie screen attached above the dusty chalkboard and, among other sundry objects, a well-used paint easel. On closer inspection of the latter, I was stunned to see “Mr. Viani” written in permanent ink on the back. It turned out that this was the same classroom in which my father, Joe Viani, had taught for years before becoming a district Child Welfare and Attendance (truant) officer. While I was in Europe, enjoying life away from home for the first time, practicing my Swedish with wonderful friends, really getting into B&W photography with my first single lens reflex (an Asahi Pentax), and catching every consciousness-expanding event that came through Sweden (Canned Heat made a memorable appearance), my father was working behind the scenes, networking with his administrative chums to get me a job at a good school, with a wonderful principal in a safe neighborhood. It’s taken years to appreciate all he did for me, and I’m astonished (and embarrassed) to have accepted everything as mere coincidence.

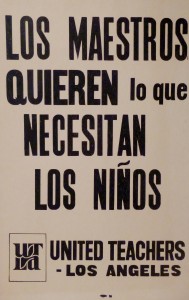

What Children Need”

Then there was the strike. I began my career as an educator that September, 1969 and, as every new teacher will confirm, it was a challenging experience. Long hours preparing for the next day, and then driving the Pasadena Freeway to my apartment on Arlington St. in Pasadena. Back and forth, everything hazy, until April 13, 1970, when my teacher’s union, United Teacher of Los Angeles (UT-LA) voted to strike. The demands were mostly contractual, asking for a top salary raise from $13,650 to around $20,000 in addition to wanting reduced classroom size and increased spending on reading and other programs. The result was that teachers got a 5% pay raise, which was what the district originally offered. They also gained advisory councils and reading programs. Teachers suffered in the short-term, however, sacrificing about $1,100 each in earnings for being on strike. The strike lasted four and a half weeks, and led to a mutually-satisfactory contract that was, alas, subsequently thrown out by the courts. The frustration seeing colleagues (administrators, counselors, and other non-teaching professionals) crossing the picket lines was terribly demoralizing. To be truthful, the loss of salary for a single person driving a hand-me-down VW bug wasn’t too painful but my Swedish-influenced idealism and a growing awareness of the United State’s role in global chaos got me thinking about alternatives to my nicely choreographed lifestyle.

When I first enrolled at LA State in the fall of 1963, I took general education survey courses required of all freshmen. While sitting in a ridiculously boring speech class, an announcement interrupted class informing us that President Kennedy had been shot in Dallas. Kennedy was a hero to those of us who’d just earned the right to vote and, among other things characterizing his short ride at the top, his inaugural address still resonated with me: “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” The frustration of having wasted nearly 5 weeks on a picket line dutifully displaying my strike sign, was the wakeup call. I hated the strike but it was a matter of principal that forced my hand. The Peace Corps was recruiting volunteers who had actual teaching experience (as opposed to the generic BA generalists), so I applied, was accepted, and secured a 2-year leave of absence from my job and a draft deferment to boot. Training in Pepeekeo, Hawaii, began in August, and I was on my way.

Epilogue: We were sworn in during a staging session at San Jose State College and my parents attended the ceremony. After a heavy night of partying, I would have missed my flight but for my parents’ intervention. I may have been an idealist but was, in reality, just a kid dodging one life-changing bullet at a time. Thinking back, I shudder about what might have happened had it not been for my wonderful parents—just being there while subtly preparing ME for parenthood.

Note: the journey continues on my first day as a Peace Corps Volunteer.