This post supports the presentation I made on 10/31/16 in the OLLI class, Beyond Tourism. The focus of my talk was how our overseas teaching assignment became one even more fascinating—overseas parenting.

After several years teaching in the Los Angeles School District, we weren’t happy with the direction our careers were heading. An upstairs neighbor in our apartment complex had recently returned from a 2-year teaching assignment in Isfahan, Iran. She loved it and we enjoyed basking in her apartment’s late afternoon sun exposure and listening to her tales. She enticed us with stories about small class sizes, exotic travel opportunities, luxurious cuisine, and her flat was generously decorated with Persian art, carpets, and ethnic articles purchased during the adventure. We’d been vetted for a similar gig with International Schools Services and the clincher was our face-to-face interview with Bill Schultheis, the President of ISS.

After several years teaching in the Los Angeles School District, we weren’t happy with the direction our careers were heading. An upstairs neighbor in our apartment complex had recently returned from a 2-year teaching assignment in Isfahan, Iran. She loved it and we enjoyed basking in her apartment’s late afternoon sun exposure and listening to her tales. She enticed us with stories about small class sizes, exotic travel opportunities, luxurious cuisine, and her flat was generously decorated with Persian art, carpets, and ethnic articles purchased during the adventure. We’d been vetted for a similar gig with International Schools Services and the clincher was our face-to-face interview with Bill Schultheis, the President of ISS.

Bill was recruiting on the west coast and kindly visited us in our apartment instead of in a sterile airport hotel room where most interviews take place. We sat around our oak table and he laid out the details of the job—co-teaching a grade 2-3 blended classroom at Pasir Ridge School in Balikpapan, a tiny port city in Indonesian Borneo. The school had 100 students in grades K-8. It was staffed by ten “overseas hired” teachers plus a locally-hired Indonesian culture, art, and language instructor. We would be living on Pasir Ridge, a recently constructed compound of houses and apartments designed especially for managerial-level employees of Unocal, a subsidiary of Union Oil Company of California. The school would be directly across from our apartment, separated by the athletic field and tennis courts. We’d have access to the club, restaurant, squash courts, swimming pool, and locally-hired Indonesians who would prepare our meals and keep things tidy. Union drivers would shuttle us to the coastal town of Balikpapan for shopping and recreation. There was only one catch: Unocal was a pretty conservative company and the 50 or so expats living there wouldn’t look favorably on us not being married. So he proposed for us. Sorta. It came out like, “What do you say?”

It was spring, 1977, and we would be permanently leaving LA, our birthplaces, and our parents, siblings, and lifetime friends. We completed our contracts with Los Angeles Unified School District and said farewell to Pasadena and a storage unit full of stuff. The latter is one of the more expensive perks provided “overseas hire” teaching couples. In exchange, ISS extracted compensation by having us fill out reams of visa applications and required that we reapply for new passports (probably for all the extra pages required for the myriad visa stamps). With all necessary documentation in hand, we departed the end of July for a 3-week self-guided mini-tour through Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, and finally arrived in Singapore on the 19th of August.

It was spring, 1977, and we would be permanently leaving LA, our birthplaces, and our parents, siblings, and lifetime friends. We completed our contracts with Los Angeles Unified School District and said farewell to Pasadena and a storage unit full of stuff. The latter is one of the more expensive perks provided “overseas hire” teaching couples. In exchange, ISS extracted compensation by having us fill out reams of visa applications and required that we reapply for new passports (probably for all the extra pages required for the myriad visa stamps). With all necessary documentation in hand, we departed the end of July for a 3-week self-guided mini-tour through Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, and finally arrived in Singapore on the 19th of August.

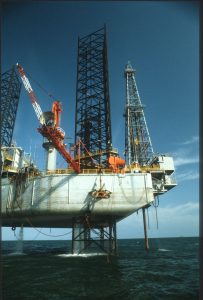

Unocal maintained a corporate office in the Shaw Centre administered by the extremely capable and wonderful Angie Chan. All staff whose destination was Balikpapan passed through that office and were housed in nearby hotels. The oil industry was lucrative in the late 70’s, and Union had several production wells in Indonesia that were staffed by crews shuttling in an out on rotations of 2 weeks on, 2 weeks off. Where they traveled during their “off” week was their business, and I knew a couple guys who beelined it to Austria in the winter months to ski during their 2 weeks off. When “on”, these skilled oil hands worked 12-hour shifts every day, meals and lodging provided. They worked, slept, and banked a ton of cash. We would occasionally see them in the Singapore office, on the charter flight, or on the Pasir Ridge campus, but usually they transferred from the airport directly to crew boats that took them off-shore. In addition to the production platforms, Unocal had a large staff of geologists and geophysicists living in Balikpapan whose primary role was exploration.

Unocal maintained a corporate office in the Shaw Centre administered by the extremely capable and wonderful Angie Chan. All staff whose destination was Balikpapan passed through that office and were housed in nearby hotels. The oil industry was lucrative in the late 70’s, and Union had several production wells in Indonesia that were staffed by crews shuttling in an out on rotations of 2 weeks on, 2 weeks off. Where they traveled during their “off” week was their business, and I knew a couple guys who beelined it to Austria in the winter months to ski during their 2 weeks off. When “on”, these skilled oil hands worked 12-hour shifts every day, meals and lodging provided. They worked, slept, and banked a ton of cash. We would occasionally see them in the Singapore office, on the charter flight, or on the Pasir Ridge campus, but usually they transferred from the airport directly to crew boats that took them off-shore. In addition to the production platforms, Unocal had a large staff of geologists and geophysicists living in Balikpapan whose primary role was exploration.

While some of these professional staff were Indonesian (often graduates of American universities and fluently conversant in English), a predominance were employees of Union Oil of California on special overseas assignments. These lucrative contracts, usually 2-years, were compelling for more than the tax-free income. In order to attract managerial-level staff overseas, Unocal provided comfortable housing and a K-8 school featuring a stateside curriculum that encouraged entire families to live abroad. Pasir Ridge housed both expat housing and the main office and closely resembled a gated community in the US. In addition to the office were a combination of stand-alone houses and 3-floored apartments, a commissary, health clinic, restaurant and bar, and all the recreational amenities one could wish for. A group of English engineers missed their squash courts and Unocal built a first-rate facility. Some of the single men were members of bowling leagues back home, so Unocal built a 4-lane bowling alley. For families, there was an Olympic-sized swimming facility that the school used as part of the PE curriculum. Unocal fielded a uniformed softball team, hosted tennis tournaments, and introduced some of us foreigners to games of cricket, pétanque (French version of bocce) and soccer. The latter is very popular in Indonesia, and the local team composed of Indonesian staff made it perfectly clear how unskilled most of us were.

While some of these professional staff were Indonesian (often graduates of American universities and fluently conversant in English), a predominance were employees of Union Oil of California on special overseas assignments. These lucrative contracts, usually 2-years, were compelling for more than the tax-free income. In order to attract managerial-level staff overseas, Unocal provided comfortable housing and a K-8 school featuring a stateside curriculum that encouraged entire families to live abroad. Pasir Ridge housed both expat housing and the main office and closely resembled a gated community in the US. In addition to the office were a combination of stand-alone houses and 3-floored apartments, a commissary, health clinic, restaurant and bar, and all the recreational amenities one could wish for. A group of English engineers missed their squash courts and Unocal built a first-rate facility. Some of the single men were members of bowling leagues back home, so Unocal built a 4-lane bowling alley. For families, there was an Olympic-sized swimming facility that the school used as part of the PE curriculum. Unocal fielded a uniformed softball team, hosted tennis tournaments, and introduced some of us foreigners to games of cricket, pétanque (French version of bocce) and soccer. The latter is very popular in Indonesia, and the local team composed of Indonesian staff made it perfectly clear how unskilled most of us were.

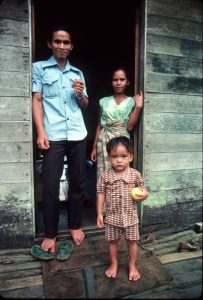

Borneo is the 3rd largest island in the world (after Greenland and New Guinea) and is politically divided among 3 countries: Malaysia and Brunei in the north, and Indonesia comprising 73% of the island to the east and south. Covering much of the territory is one of the oldest rainforests in the world. Its indigenous population are seven ethnic divisions of Dayaks, and living along the coast are a mixture of immigrants, many of whom arrived as part of the government’s Transmigration program. An attempt to alleviate overcrowding in Java, poor landless people were resettled in villages in more remote regions of Indonesia, and over a million ended up in Kalimantan. Often lacking farming skills, their plight was exacerbated because the soil of heavily overgrazed rainforest paled in comparison to the rich volcanic soil of Java. Tapioca was a popular crop that fared better than most and we saw plots of the spindly plant everywhere.

Borneo is the 3rd largest island in the world (after Greenland and New Guinea) and is politically divided among 3 countries: Malaysia and Brunei in the north, and Indonesia comprising 73% of the island to the east and south. Covering much of the territory is one of the oldest rainforests in the world. Its indigenous population are seven ethnic divisions of Dayaks, and living along the coast are a mixture of immigrants, many of whom arrived as part of the government’s Transmigration program. An attempt to alleviate overcrowding in Java, poor landless people were resettled in villages in more remote regions of Indonesia, and over a million ended up in Kalimantan. Often lacking farming skills, their plight was exacerbated because the soil of heavily overgrazed rainforest paled in comparison to the rich volcanic soil of Java. Tapioca was a popular crop that fared better than most and we saw plots of the spindly plant everywhere.

A tolerant version of Islam prevailed among these newcomers, although a traditional animist belief was sacred to the indigenous Dayaks. While traveling to visit 2 socio-biologists working in the interior, we saw 8’ carved wooden statues along forest paths both guarding tribal land and placed with the hope of gaining favor with hunting gods. A common destination for Christian missionaries were those remote Dayak villages, and it was particularly challenging getting supplies to their densely-forested outposts. The solution was a short takeoff and landing airplane called a Trislander that featured 2 engines forward and one aft. The rear engine really helped the plane rise quickly from the short runways carved out of the forest. On one occasion we were able to tag along on a flight well into the interior. After watching that amazing plane take off almost vertically we spent 6 days trekking from village to village en-route to the Mahakam River that flows 600 miles from central Kalimantan to the Makassar Straits. We slept in village schoolrooms, medical clinics, and traveled with one section of our backpack filled with used tennis balls we tossed to thrilled children who allowed us to practice our entry-level language skills. They would scamper off down the trail and when we finally arrived in a village, everyone would know all about us, where we’d traveled from and where we were heading. The basis for all this interaction was our fundamental Indonesian language skills upon which we relied throughout our 5 years living there. Finally arriving at the Mahakam river, we boarded a local boat and spent 2 days traveling to Samarinda accompanied by a few other passengers and a cargo of rattan vines used to make furniture and, among the Dayaks, beautifully woven baskets.

A tolerant version of Islam prevailed among these newcomers, although a traditional animist belief was sacred to the indigenous Dayaks. While traveling to visit 2 socio-biologists working in the interior, we saw 8’ carved wooden statues along forest paths both guarding tribal land and placed with the hope of gaining favor with hunting gods. A common destination for Christian missionaries were those remote Dayak villages, and it was particularly challenging getting supplies to their densely-forested outposts. The solution was a short takeoff and landing airplane called a Trislander that featured 2 engines forward and one aft. The rear engine really helped the plane rise quickly from the short runways carved out of the forest. On one occasion we were able to tag along on a flight well into the interior. After watching that amazing plane take off almost vertically we spent 6 days trekking from village to village en-route to the Mahakam River that flows 600 miles from central Kalimantan to the Makassar Straits. We slept in village schoolrooms, medical clinics, and traveled with one section of our backpack filled with used tennis balls we tossed to thrilled children who allowed us to practice our entry-level language skills. They would scamper off down the trail and when we finally arrived in a village, everyone would know all about us, where we’d traveled from and where we were heading. The basis for all this interaction was our fundamental Indonesian language skills upon which we relied throughout our 5 years living there. Finally arriving at the Mahakam river, we boarded a local boat and spent 2 days traveling to Samarinda accompanied by a few other passengers and a cargo of rattan vines used to make furniture and, among the Dayaks, beautifully woven baskets.

School breaks offered us ample time to explore that enormous country, and on several occasions we visited the island of Flores, part of what is called Nusa Tenggara and located several islands east of Bali. A predominantly Catholic population, Flores was an outpost frequented for hundreds of years by Portuguese mariners involved in the spice trade. Unlike rainy Borneo, Flores had a temperate climate and the people adapted to draught conditions. Due to a limited supply of lumber, men constructed dwellings from hand-made mud bricks and tended cotton fields. The women spun the cotton, colored it with dyes made from local plants, and used backstrap looms to weave panels of cloth that were sewn into sarongs, their traditional garment. We became fascinated with the ikat technique, the friendly people, and the geographically diverse countryside. On our first visit, we stayed in a basic traveler’s accommodation next door to the theater that broadcast the soundtrack of the movie for those unable to pay admission. Covered by a cascading mosquito net, we dozed on and off to a concert of nearby insects and animated dialog.

School breaks offered us ample time to explore that enormous country, and on several occasions we visited the island of Flores, part of what is called Nusa Tenggara and located several islands east of Bali. A predominantly Catholic population, Flores was an outpost frequented for hundreds of years by Portuguese mariners involved in the spice trade. Unlike rainy Borneo, Flores had a temperate climate and the people adapted to draught conditions. Due to a limited supply of lumber, men constructed dwellings from hand-made mud bricks and tended cotton fields. The women spun the cotton, colored it with dyes made from local plants, and used backstrap looms to weave panels of cloth that were sewn into sarongs, their traditional garment. We became fascinated with the ikat technique, the friendly people, and the geographically diverse countryside. On our first visit, we stayed in a basic traveler’s accommodation next door to the theater that broadcast the soundtrack of the movie for those unable to pay admission. Covered by a cascading mosquito net, we dozed on and off to a concert of nearby insects and animated dialog.

During a visit to the open-air market, we met an Italian couple who managed the Sea World Club not far from where we were staying in Maumere, a coastal town featuring a long, languid coastline along the northern part of the island. We were invited to a fabulous Eurasian meal and learned the facility was owned by the Catholic parish administered by a German missionary and patron of local art. He introduced us to the sophistication of the ikat process and had an extensive inventory of textiles available for purchase by groups of European tourists who stayed at the resort, slept in palm cottages, dined on exquisite cuisine, snorkeled in world-class coral reefs, and spent considerable sums at Pater Bollan’s ikat outlet.

During a visit to the open-air market, we met an Italian couple who managed the Sea World Club not far from where we were staying in Maumere, a coastal town featuring a long, languid coastline along the northern part of the island. We were invited to a fabulous Eurasian meal and learned the facility was owned by the Catholic parish administered by a German missionary and patron of local art. He introduced us to the sophistication of the ikat process and had an extensive inventory of textiles available for purchase by groups of European tourists who stayed at the resort, slept in palm cottages, dined on exquisite cuisine, snorkeled in world-class coral reefs, and spent considerable sums at Pater Bollan’s ikat outlet.

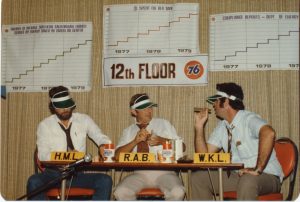

Bear in mind that Pasir Ridge wasn’t lacking when it came to culture. During the school term activities flourished, limited only by the imagination of the community. An active theater group performed both for adults and children with props constructed locally in Unocal’s woodworking and metal fabrication shops. We’d design a set, submit it, and in no time there it was. Costumes were sewn by skilled tailors in nearby Balikpapan. Again it was show them a photo or drawing and they’d meet our expectations and then some. Mind you, these tailors were using foot-pedaled machines because power was unpredictable. When corporate big shots visited from Los Angeles, there would be gala dinners with entertainment provided by local talent. Sooney and I teamed up with a production manager (a good guitar picker from Bakersfield) and an Indonesian geologist from Sumatra. Sumatran music is rich in harmonies and he adapted his ear to ballads we arranged from familiar tunes by Willie Nelson, Roy Orbison, Linda Ronstadt, Emmylou Harris, and many more, all of which the lubricated audience would happily sing along with. Oh, and did I mention there were 10 teachers and approximately 100 students? A teacher/student ratio unheard of in the US. And the parents were thrilled.

Bear in mind that Pasir Ridge wasn’t lacking when it came to culture. During the school term activities flourished, limited only by the imagination of the community. An active theater group performed both for adults and children with props constructed locally in Unocal’s woodworking and metal fabrication shops. We’d design a set, submit it, and in no time there it was. Costumes were sewn by skilled tailors in nearby Balikpapan. Again it was show them a photo or drawing and they’d meet our expectations and then some. Mind you, these tailors were using foot-pedaled machines because power was unpredictable. When corporate big shots visited from Los Angeles, there would be gala dinners with entertainment provided by local talent. Sooney and I teamed up with a production manager (a good guitar picker from Bakersfield) and an Indonesian geologist from Sumatra. Sumatran music is rich in harmonies and he adapted his ear to ballads we arranged from familiar tunes by Willie Nelson, Roy Orbison, Linda Ronstadt, Emmylou Harris, and many more, all of which the lubricated audience would happily sing along with. Oh, and did I mention there were 10 teachers and approximately 100 students? A teacher/student ratio unheard of in the US. And the parents were thrilled.

Indonesian law had strict rules about women working in a male environment, Unocal, because of its affiliation with Pertamina, the Indonesian state-owned oil and natural gas corporation based in Jakarta, did its best to comply. Women teachers were permitted contracts because ISS required professional licensure by international accreditation teams. The oil industry was different, and males generally filled department staffing vacancies. I recall one situation where a married couple, both geologists, lived and worked in our community for a year; he in the Unocal office on campus, she in her home office. For this reason many of the expat wives, unable to work and often highly skilled and/or educated, contributed time at school as classroom volunteers, as educational assistants, and as participants on field trips.

One trip remains particularly memorable. I was teaching 6th grade and our thematic unit was Indonesian art. The father of one of my students was the Drilling Manager who had access to an airplane. The pilot and plane were on-call Monday-Saturday and remained unused on Sundays. One afternoon, inhaling an ice-cold Bir Bintang after a steamy game of squash, I pitched my idea how nicely a visit to Flores would fit into my Social Studies curriculum. I explained how feasibly the plane could fly the 19 middle-school students, a couple co-teachers, and several of the children’s mothers for a week-long visit of snorkeling, campfires on the beach, and excursions to a nearby dormant volcano with 3 lakes in the caldera (each a different color). He ultimately agreed, and off we flew, from one Sunday to the next. We even integrated the music curriculum by singing all our chorus songs around an evening campfire, thoroughly entertaining residents from nearby villages who joined us on the beach. International high schools generally budget enormous sums to fly their teams to athletic competitions to distant cities, often in other countries. It would be highly unusual for a middle schools to pull off a 2,500 mile field trip like we did to Flores. But that’s what’s remarkable about those schools—and those jobs. If you wanted something, you did your best to sell your idea. Field trips? Local theater? I suppose one could argue we all paid for it at the pump, but it was a good ride along the way.

One trip remains particularly memorable. I was teaching 6th grade and our thematic unit was Indonesian art. The father of one of my students was the Drilling Manager who had access to an airplane. The pilot and plane were on-call Monday-Saturday and remained unused on Sundays. One afternoon, inhaling an ice-cold Bir Bintang after a steamy game of squash, I pitched my idea how nicely a visit to Flores would fit into my Social Studies curriculum. I explained how feasibly the plane could fly the 19 middle-school students, a couple co-teachers, and several of the children’s mothers for a week-long visit of snorkeling, campfires on the beach, and excursions to a nearby dormant volcano with 3 lakes in the caldera (each a different color). He ultimately agreed, and off we flew, from one Sunday to the next. We even integrated the music curriculum by singing all our chorus songs around an evening campfire, thoroughly entertaining residents from nearby villages who joined us on the beach. International high schools generally budget enormous sums to fly their teams to athletic competitions to distant cities, often in other countries. It would be highly unusual for a middle schools to pull off a 2,500 mile field trip like we did to Flores. But that’s what’s remarkable about those schools—and those jobs. If you wanted something, you did your best to sell your idea. Field trips? Local theater? I suppose one could argue we all paid for it at the pump, but it was a good ride along the way.

In addition to traveling during the school term, the Unocal administration creatively designed the school calendar to promote travel within Indonesia during school breaks. Both the months of December and April were school holidays, too short for trips home to visit family and perfect for seasonal travel throughout Indonesia. Alas, for some of the expat community, “going to town” meant jumping on the twice-weekly charter jet to Singapore. We saw it differently, and a 15-minute ride dropped us in the middle of Balikpapan, a hybrid town of many different Indonesian cultures. We loved the diversity, others didn’t. Aside from wonderful seafood restaurants featuring ikan bakar (barbecued seafood especially popular in nearby Sulawesi) and the frequently visited tailors, I particularly enjoyed regular visits to “art” shops. Items of antiquity (and others not so much) were searched for and purchased by agents working for the shop proprietors. Of particular interest to us were Dayak artifacts, especially rattan sleeping mats and the soft baskets exquisitely woven long ago by genuine masters. Dayak backpacks featured a patina that could only come from repeated contact with the skin of the former owner. Another collectible (for us) were ceramic plates that were most likely recovered from ship wrecks succumbing to treacherous water while participating in the spice trade centuries ago. I never knew what the proprietor’s agents would locate on their buying forays into the interior of Borneo, and we’re still using some found items to this day. At one point, the Manager of Administration enacted a program where those interested could submit a travel itinerary to visit anyplace in Indonesia, a country consisting of 6,000 inhabited islands and geographically as long as the continental United States. If approved, Unocal paid for the flight and added a per-diem to cover meals and lodging. I traveled as far east as Timor, stopping off in Sumba, Surabaya, and connected with Sooney in Yogyakarta where she’d spent the month studying batik (and Bahasa Indonesia) with Trihono, a living cultural treasure. We’d return from these adventures and wonder why some expats were content with shopping sprees in a bustling mall. Singapore does, however, hold a special place in our hearts because our daughter, Alicia, was born there in the spring of our 4th year.

In addition to traveling during the school term, the Unocal administration creatively designed the school calendar to promote travel within Indonesia during school breaks. Both the months of December and April were school holidays, too short for trips home to visit family and perfect for seasonal travel throughout Indonesia. Alas, for some of the expat community, “going to town” meant jumping on the twice-weekly charter jet to Singapore. We saw it differently, and a 15-minute ride dropped us in the middle of Balikpapan, a hybrid town of many different Indonesian cultures. We loved the diversity, others didn’t. Aside from wonderful seafood restaurants featuring ikan bakar (barbecued seafood especially popular in nearby Sulawesi) and the frequently visited tailors, I particularly enjoyed regular visits to “art” shops. Items of antiquity (and others not so much) were searched for and purchased by agents working for the shop proprietors. Of particular interest to us were Dayak artifacts, especially rattan sleeping mats and the soft baskets exquisitely woven long ago by genuine masters. Dayak backpacks featured a patina that could only come from repeated contact with the skin of the former owner. Another collectible (for us) were ceramic plates that were most likely recovered from ship wrecks succumbing to treacherous water while participating in the spice trade centuries ago. I never knew what the proprietor’s agents would locate on their buying forays into the interior of Borneo, and we’re still using some found items to this day. At one point, the Manager of Administration enacted a program where those interested could submit a travel itinerary to visit anyplace in Indonesia, a country consisting of 6,000 inhabited islands and geographically as long as the continental United States. If approved, Unocal paid for the flight and added a per-diem to cover meals and lodging. I traveled as far east as Timor, stopping off in Sumba, Surabaya, and connected with Sooney in Yogyakarta where she’d spent the month studying batik (and Bahasa Indonesia) with Trihono, a living cultural treasure. We’d return from these adventures and wonder why some expats were content with shopping sprees in a bustling mall. Singapore does, however, hold a special place in our hearts because our daughter, Alicia, was born there in the spring of our 4th year.

With a population of 145 million in 1980, it’s safe to say a few healthy deliveries occurred on any given day. Union Oil, however, mandated that births to overseas hires take place in Singapore so, in mid-May Sooney departed for a fully-paid pre-natal accommodation in a stylish high-rise overlooking Singapore bay. It was also not far from the Thompson Medical Clinic where the delivery took place. As the school term continued through the end of March, I joined her two weeks prior to Alicia’s arrival on April 13. A couple weeks after the birth, Sooney returned to Balikpapan accompanied by her parents visiting from Montana. At the last minute, I was called away on an medical emergency to be with my father in Los Angeles and assist my mother for the difficult times ahead. My return in early June found Sooney and sweet Alicia comfortable in our apartment, well tended to by our house keeper, Emmy, and a longtime family friend and pembantu, Narti, who helped with the infant son of our dear friends in town. The academic term ended soon after, and we flew first class to Los Angeles for the first and only time, Alicia comfortably bundled in a fiber basket at our feet.

With a population of 145 million in 1980, it’s safe to say a few healthy deliveries occurred on any given day. Union Oil, however, mandated that births to overseas hires take place in Singapore so, in mid-May Sooney departed for a fully-paid pre-natal accommodation in a stylish high-rise overlooking Singapore bay. It was also not far from the Thompson Medical Clinic where the delivery took place. As the school term continued through the end of March, I joined her two weeks prior to Alicia’s arrival on April 13. A couple weeks after the birth, Sooney returned to Balikpapan accompanied by her parents visiting from Montana. At the last minute, I was called away on an medical emergency to be with my father in Los Angeles and assist my mother for the difficult times ahead. My return in early June found Sooney and sweet Alicia comfortable in our apartment, well tended to by our house keeper, Emmy, and a longtime family friend and pembantu, Narti, who helped with the infant son of our dear friends in town. The academic term ended soon after, and we flew first class to Los Angeles for the first and only time, Alicia comfortably bundled in a fiber basket at our feet.

The following teaching year was completely different from the previous four. We both resumed full-time teaching, and having an apartment a couple hundred yards from school made Sooney’s regular visits home much easier. Our meals were thankfully prepared on schedule and Alicia was attached to Narti’s waist by a batik selendang, a long strip of fabric tied around the neck. When it was nap time, Narti simply lay down and the two of them slept peacefully. We toned down our recreational activities somewhat and enjoyed our final year on Pasir Ridge photographing our daughter, embracing her daily changes, and relaxing among our garden of orchids inhabiting the decks of our apartment. We still had two school breaks to look forward to that final year, and Alicia became an integral part of our journeys.

The following teaching year was completely different from the previous four. We both resumed full-time teaching, and having an apartment a couple hundred yards from school made Sooney’s regular visits home much easier. Our meals were thankfully prepared on schedule and Alicia was attached to Narti’s waist by a batik selendang, a long strip of fabric tied around the neck. When it was nap time, Narti simply lay down and the two of them slept peacefully. We toned down our recreational activities somewhat and enjoyed our final year on Pasir Ridge photographing our daughter, embracing her daily changes, and relaxing among our garden of orchids inhabiting the decks of our apartment. We still had two school breaks to look forward to that final year, and Alicia became an integral part of our journeys.

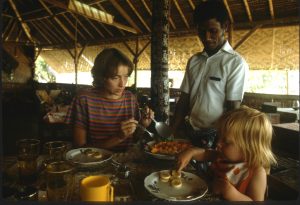

One memorable trip was after we’d completed our contract year and were staying with our friends, Rachmat & Emma for several months before returning to the US. We returned to Flores to do research for a book on the ikat weaving culture, and Alicia fit right into the itinerary. We stayed at the Sea World Club where I’d taken my middle school students only months earlier, only this time we had the place to ourselves and Alicia, now 14 months old, soon learned how fun it was to drop a spoon and watch how rapidly the Indonesian dining staff would replace it on her tray. This didn’t last long and her tears gave way to using her fingers for the rest of the meal. Our daytime activities included visits to the local market and walks along the beach where Alicia was often the center of attention with her red hair and light complexion. Locals would give her good-natured squeezes on the cheek that didn’t always result as expected. I recall she didn’t enjoy those signs of affection and her tears temporarily put an end to that.

One memorable trip was after we’d completed our contract year and were staying with our friends, Rachmat & Emma for several months before returning to the US. We returned to Flores to do research for a book on the ikat weaving culture, and Alicia fit right into the itinerary. We stayed at the Sea World Club where I’d taken my middle school students only months earlier, only this time we had the place to ourselves and Alicia, now 14 months old, soon learned how fun it was to drop a spoon and watch how rapidly the Indonesian dining staff would replace it on her tray. This didn’t last long and her tears gave way to using her fingers for the rest of the meal. Our daytime activities included visits to the local market and walks along the beach where Alicia was often the center of attention with her red hair and light complexion. Locals would give her good-natured squeezes on the cheek that didn’t always result as expected. I recall she didn’t enjoy those signs of affection and her tears temporarily put an end to that.

An important consideration for international teachers is the time (and distance) from loved ones back home. Our summers were often hectic because we had family in Irvine, CA, and Whitefish, MT, and did our best to share quality time with both sets of grandparents. 35 years ago, flights connecting LA and Singapore required an overnight layover. Because we frequently flew Japan Airlines, that meant a night at the JAL Narita hotel, room and board provided by the airline. We loved the compactness of these transit hotels, and marveled how the shower and commode were all one room with an 8” transom keeping the water out of the small sleeping room (but annoyingly NOT off the toilet seat). Once home, we’d set up a daunting social itinerary, call those we were unable to visit, shop for essentials, and literally cram all our purchases into metal foot lockers that Unocal shipped as accompanying baggage. They needed to be checked in, however, and there was always stress the end of August when departure was imminent and we had a couple 60-pound metal boxes jammed into my parent’s car for our sad journey to the airport. One return didn’t quite work out as planned although years of international globe-trotting prepared us for that. En-route to LAX from Orange County on the notoriously crowded 405 freeway, we got caught in traffic and saw our JAL flight ascending above us as we approached the airport. My dad was fit to be tied, but I assured him all would work out and waved a smile as he drove off (I’m sure shaking his head in bewilderment). After all, we were, by now, experienced international travelers who learned to convert misfortunes into blessings. Tickets in hand and Sooney left guarding our mountain of luggage, I went from counter to counter looking for a flight. Within 15 minutes I scored seats on Thai International’s Royal Orchid Express that included the obligatory overnight in Bangkok. The next morning, our connecting flight to Singapore arrived well before the JAL because of how much shorter the final leg was. I can’t imagine airlines being quite as forgiving these days, and look back on travel in the late 70’s as an era lost but not forgotten.

An important consideration for international teachers is the time (and distance) from loved ones back home. Our summers were often hectic because we had family in Irvine, CA, and Whitefish, MT, and did our best to share quality time with both sets of grandparents. 35 years ago, flights connecting LA and Singapore required an overnight layover. Because we frequently flew Japan Airlines, that meant a night at the JAL Narita hotel, room and board provided by the airline. We loved the compactness of these transit hotels, and marveled how the shower and commode were all one room with an 8” transom keeping the water out of the small sleeping room (but annoyingly NOT off the toilet seat). Once home, we’d set up a daunting social itinerary, call those we were unable to visit, shop for essentials, and literally cram all our purchases into metal foot lockers that Unocal shipped as accompanying baggage. They needed to be checked in, however, and there was always stress the end of August when departure was imminent and we had a couple 60-pound metal boxes jammed into my parent’s car for our sad journey to the airport. One return didn’t quite work out as planned although years of international globe-trotting prepared us for that. En-route to LAX from Orange County on the notoriously crowded 405 freeway, we got caught in traffic and saw our JAL flight ascending above us as we approached the airport. My dad was fit to be tied, but I assured him all would work out and waved a smile as he drove off (I’m sure shaking his head in bewilderment). After all, we were, by now, experienced international travelers who learned to convert misfortunes into blessings. Tickets in hand and Sooney left guarding our mountain of luggage, I went from counter to counter looking for a flight. Within 15 minutes I scored seats on Thai International’s Royal Orchid Express that included the obligatory overnight in Bangkok. The next morning, our connecting flight to Singapore arrived well before the JAL because of how much shorter the final leg was. I can’t imagine airlines being quite as forgiving these days, and look back on travel in the late 70’s as an era lost but not forgotten.

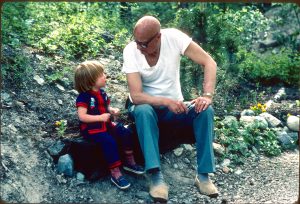

After 5 years teaching and exploring Indonesia, we decided to return with our 18-month-old daughter to the US to spend a winter with Sooney’s parents in Whitefish, MT. Her father was traveling frequently to San Francisco for medical reasons and we often had their spacious house to ourselves, complete with a massive deck overlooking Whitefish Lake and Big Mountain Ski resort rising from the far shore. Compared to some of the places we’d visited during the previous 5 years, Montana surprised us with “foreign” experiences that might have qualified as international travel had it not been for the common language. Of course, having 2 loving grandparents around much of the time helped us slip back into the good ol’ USA. We enrolled Alicia in a play group and visited Ma Brown regularly to collect eggs and play with her kittens. When winter set in, I worked in construction and the boss and I would take the day off whenever new powder fell on the mountain. After a year, we felt drawn back into teaching and I padded my resumé by completing requirements for the elementary administrative credential from the University of Montana in Missoula. In February, 1984, we attended the ISS recruiting fair in New York City and landed positions to teach in the elementary program at the Canadian Academy, a K-12 international school in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. With jobs secure, we relocated to Orange County to spend the remainder of our sabbatical with my mother. While there, I attended a 3-week writing workshop at the University of California, Irvine, that a few years later morphed into the National Writing Project. Looking back, that exposure to the writing process was probably the most important academic decision I’d make as writing became a unifying thread throughout my remaining 20 years in education.

After 5 years teaching and exploring Indonesia, we decided to return with our 18-month-old daughter to the US to spend a winter with Sooney’s parents in Whitefish, MT. Her father was traveling frequently to San Francisco for medical reasons and we often had their spacious house to ourselves, complete with a massive deck overlooking Whitefish Lake and Big Mountain Ski resort rising from the far shore. Compared to some of the places we’d visited during the previous 5 years, Montana surprised us with “foreign” experiences that might have qualified as international travel had it not been for the common language. Of course, having 2 loving grandparents around much of the time helped us slip back into the good ol’ USA. We enrolled Alicia in a play group and visited Ma Brown regularly to collect eggs and play with her kittens. When winter set in, I worked in construction and the boss and I would take the day off whenever new powder fell on the mountain. After a year, we felt drawn back into teaching and I padded my resumé by completing requirements for the elementary administrative credential from the University of Montana in Missoula. In February, 1984, we attended the ISS recruiting fair in New York City and landed positions to teach in the elementary program at the Canadian Academy, a K-12 international school in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. With jobs secure, we relocated to Orange County to spend the remainder of our sabbatical with my mother. While there, I attended a 3-week writing workshop at the University of California, Irvine, that a few years later morphed into the National Writing Project. Looking back, that exposure to the writing process was probably the most important academic decision I’d make as writing became a unifying thread throughout my remaining 20 years in education.

The transition to Japan was reminiscent of our previous 5-year gig in Indonesia, although not without some drama. We were guaranteed by the Headmaster (who, we learned, was fired shortly after he hired us) that our teaching calendar would align with that of the Japanese Yochien, the wonderful preschools in which we’d enroll Alicia. That sadly wasn’t the case and, combined with the heat, humidity, and hills that characterize coastal Kobe in early August, added to our anxiety. We dutifully spent hours preparing our classrooms for the significantly larger class sizes we were unaccustomed to. Alicia, bless her heart, loved the Yochien and we quickly made a lasting friendship with the Yanagida family whose daughter, Ayuri, was Alicia’s classmate. I’d purchased a small red scooter and would drop Alicia off at their house in the morning long after Sooney had left to prepare for her 1st graders. All went well for the first semester, but since CA’s spring break didn’t conform with the Yochien’s month-long spring vacation, we had a problem. Our headmaster, up to his ears in adapting to a new position not even remotely similar to his previous assignment in Bangladesh, felt our frustration and helped us work things out. My mother was living alone in California and missed her granddaughter. My father died the summer after Alicia was born, so Natalie very willingly accepted our offer to come live with us in Japan for the remainder of the school year. She assimilated immediately into the routine, and filled her days with English conversation groups and keeping fit walking Alicia home along hilly streets to our tiny apartment. We should have anticipated lilliputian accommodations based on several overnights at the compact JAL transit hotels. Our apartment was no less compact. My dear mother lay on her futon and both her feet and head were mere inches from concrete walls “papered” with adhesive vinyl shelf paper. Our heating came from a wall-mounted propane unit, causing the walls to weep from the condensation generated by the heater. Everything was damp and, during that first bitterly cold winter, I developed Pneumonia that knocked me down for a couple weeks. The four of us prevailed, however, and spring embraced us with city-wide bouquet of cherry blossoms. Sooney was fortunately relieved of her contractual obligation for the next two years and we got along just fine, sadly without my mother who’d re-entered life in a much gentler Southern California.

The transition to Japan was reminiscent of our previous 5-year gig in Indonesia, although not without some drama. We were guaranteed by the Headmaster (who, we learned, was fired shortly after he hired us) that our teaching calendar would align with that of the Japanese Yochien, the wonderful preschools in which we’d enroll Alicia. That sadly wasn’t the case and, combined with the heat, humidity, and hills that characterize coastal Kobe in early August, added to our anxiety. We dutifully spent hours preparing our classrooms for the significantly larger class sizes we were unaccustomed to. Alicia, bless her heart, loved the Yochien and we quickly made a lasting friendship with the Yanagida family whose daughter, Ayuri, was Alicia’s classmate. I’d purchased a small red scooter and would drop Alicia off at their house in the morning long after Sooney had left to prepare for her 1st graders. All went well for the first semester, but since CA’s spring break didn’t conform with the Yochien’s month-long spring vacation, we had a problem. Our headmaster, up to his ears in adapting to a new position not even remotely similar to his previous assignment in Bangladesh, felt our frustration and helped us work things out. My mother was living alone in California and missed her granddaughter. My father died the summer after Alicia was born, so Natalie very willingly accepted our offer to come live with us in Japan for the remainder of the school year. She assimilated immediately into the routine, and filled her days with English conversation groups and keeping fit walking Alicia home along hilly streets to our tiny apartment. We should have anticipated lilliputian accommodations based on several overnights at the compact JAL transit hotels. Our apartment was no less compact. My dear mother lay on her futon and both her feet and head were mere inches from concrete walls “papered” with adhesive vinyl shelf paper. Our heating came from a wall-mounted propane unit, causing the walls to weep from the condensation generated by the heater. Everything was damp and, during that first bitterly cold winter, I developed Pneumonia that knocked me down for a couple weeks. The four of us prevailed, however, and spring embraced us with city-wide bouquet of cherry blossoms. Sooney was fortunately relieved of her contractual obligation for the next two years and we got along just fine, sadly without my mother who’d re-entered life in a much gentler Southern California.

Our annual visits home in the summers resumed, and on local holidays we thoroughly embraced Japanese culture along with several other newly-arrived teachers. Sharing the angst, frustration, and bliss of living in a foreign country, compounded by a difficult language (Sooney was comfortably conversant after 5 years in Indonesia), we worked long hours and then immersed ourselves in Japanese culture with Alicia, our new friends, and their children. The protective country club living of Indonesia was replaced by an extended family with life-long friends with whom we’re still close. Japan is predominately mountainous, and the distance from the port of Kobe on the Inland Sea to our apartment in the foothills was less than a mile. Behind us was a coastal range topped by Mount Rokkō and its local ski facility. Skiing quite naturally became a favorite family recreational activity with a funicular providing affordable transportation to and from the hill. During the off season, trails beginning directly behind our hillside campus led to Arima Onsen, a popular bathing spot. We would leave after breakfast, work up an appetite hiking the 4 hours and arrive just in time for some tasty noodles. It was then into the furo for several therapeutic soaks before sleeping all the way back to Kobe on the afternoon bus. On weekdays in winter, the 3 of us would walk to a local public bath where Alicia would bathe and soak with me and Sooney would join the women on the other side of a thin room divider. The women enjoyed their time without children and took turns scrubbing each other’s backs before soaking in the steamy tubs. Fathers modeled correct bathing etiquette for their children by scrubbing down twice before entering the baths. It was then another soapy scrub and, for sheer exhilaration, a few minutes in the steam room followed by a leap into the cold bath. Bundled in our heavily padded Japanese coats, our walk home was delightful because our inner core was toasty and our steamy breaths crystalized in the wintery moisture. We quickly learned the importance of placing microwave-heated rice bags beneath our futons so that warmth wasn’t wasted come bedtime.

Our annual visits home in the summers resumed, and on local holidays we thoroughly embraced Japanese culture along with several other newly-arrived teachers. Sharing the angst, frustration, and bliss of living in a foreign country, compounded by a difficult language (Sooney was comfortably conversant after 5 years in Indonesia), we worked long hours and then immersed ourselves in Japanese culture with Alicia, our new friends, and their children. The protective country club living of Indonesia was replaced by an extended family with life-long friends with whom we’re still close. Japan is predominately mountainous, and the distance from the port of Kobe on the Inland Sea to our apartment in the foothills was less than a mile. Behind us was a coastal range topped by Mount Rokkō and its local ski facility. Skiing quite naturally became a favorite family recreational activity with a funicular providing affordable transportation to and from the hill. During the off season, trails beginning directly behind our hillside campus led to Arima Onsen, a popular bathing spot. We would leave after breakfast, work up an appetite hiking the 4 hours and arrive just in time for some tasty noodles. It was then into the furo for several therapeutic soaks before sleeping all the way back to Kobe on the afternoon bus. On weekdays in winter, the 3 of us would walk to a local public bath where Alicia would bathe and soak with me and Sooney would join the women on the other side of a thin room divider. The women enjoyed their time without children and took turns scrubbing each other’s backs before soaking in the steamy tubs. Fathers modeled correct bathing etiquette for their children by scrubbing down twice before entering the baths. It was then another soapy scrub and, for sheer exhilaration, a few minutes in the steam room followed by a leap into the cold bath. Bundled in our heavily padded Japanese coats, our walk home was delightful because our inner core was toasty and our steamy breaths crystalized in the wintery moisture. We quickly learned the importance of placing microwave-heated rice bags beneath our futons so that warmth wasn’t wasted come bedtime.

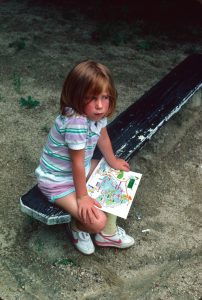

Japan is connected by a very efficient rail system that we used to explore nearby Kyoto and Hiroshima. A local bus connected us with Himeji and its gorgeous White Heron Castle that dripped with Ninja blood and housed a museum of feudal armaments. Nothing, however, immersed us so thoroughly into the Japanese culture than Bishyo Yochien, Alicia’s preschool. She was the only non-Japanese in her class, and quickly learned a survival vocabulary of Japanese. Every teacher was competent on the piano, and this resonated with Alicia’s musical genes. She returned from school each day and free-composed on our electronic keyboard, singing lyrics only she could understand. The school’s curriculum was interspersed with music that included chants and some new instruments, one of which was a small horn that included a keyboard. Alicia was comfortable at her school and was loved by her playmates and teachers. I asked her recently what she remembered about the experience. “The click-clack shoes” she instantly answered, a reference to sounds made by plastic sandals worn when using the bathroom (one never wears indoor slippers in the toilet room!). We regularly attended performances, both musical and athletic, that demonstrated the high expectations of both the teachers and parents. That common attribute made Sooney’s involvement much easier as she was released from her CA contract and immersed herself into the yochien’s parent population. She offered English language conversation groups and decorated our apartment with beautiful flower arrangements she learned at the Yochien’s Ikebana classes for parents. Her training at Pacific Oaks, an early childhood graduate program in Pasadena, inspired other extra-curricular activities she initiated at CA during those 2 years. She developed a program of music and “monkeying around” and gathered wobblers and toddlers (and their parents) in the CA gym for much more than a playgroup. There was a constant need for English instruction, and many expats found employment by simply teaching English. Being full time international school teachers, we complemented our salaries with after-hour sessions with textbook companies recording audio tapes to support English training materials. A friend in Tokyo was the project leader for an early childhood language training kit that focused on initial sounds, many of which were difficult for Japanese learners. We were flown to Tokyo, provided accommodations and a meal per-diem, and spent the day in the studio making up sounds to accompany language patterns such as, “the washing machine, the washing machine” (at which point we’d cozy up to the mic and slosh water in our mouths pretending to be a rinse cycle). Fun—and lucrative.

Japan is connected by a very efficient rail system that we used to explore nearby Kyoto and Hiroshima. A local bus connected us with Himeji and its gorgeous White Heron Castle that dripped with Ninja blood and housed a museum of feudal armaments. Nothing, however, immersed us so thoroughly into the Japanese culture than Bishyo Yochien, Alicia’s preschool. She was the only non-Japanese in her class, and quickly learned a survival vocabulary of Japanese. Every teacher was competent on the piano, and this resonated with Alicia’s musical genes. She returned from school each day and free-composed on our electronic keyboard, singing lyrics only she could understand. The school’s curriculum was interspersed with music that included chants and some new instruments, one of which was a small horn that included a keyboard. Alicia was comfortable at her school and was loved by her playmates and teachers. I asked her recently what she remembered about the experience. “The click-clack shoes” she instantly answered, a reference to sounds made by plastic sandals worn when using the bathroom (one never wears indoor slippers in the toilet room!). We regularly attended performances, both musical and athletic, that demonstrated the high expectations of both the teachers and parents. That common attribute made Sooney’s involvement much easier as she was released from her CA contract and immersed herself into the yochien’s parent population. She offered English language conversation groups and decorated our apartment with beautiful flower arrangements she learned at the Yochien’s Ikebana classes for parents. Her training at Pacific Oaks, an early childhood graduate program in Pasadena, inspired other extra-curricular activities she initiated at CA during those 2 years. She developed a program of music and “monkeying around” and gathered wobblers and toddlers (and their parents) in the CA gym for much more than a playgroup. There was a constant need for English instruction, and many expats found employment by simply teaching English. Being full time international school teachers, we complemented our salaries with after-hour sessions with textbook companies recording audio tapes to support English training materials. A friend in Tokyo was the project leader for an early childhood language training kit that focused on initial sounds, many of which were difficult for Japanese learners. We were flown to Tokyo, provided accommodations and a meal per-diem, and spent the day in the studio making up sounds to accompany language patterns such as, “the washing machine, the washing machine” (at which point we’d cozy up to the mic and slosh water in our mouths pretending to be a rinse cycle). Fun—and lucrative.

Alicia finished 2nd grade during our fifth and final year in Japan. The previous summer, Sooney attended the 3-week Oregon Writing Project in Ashland, OR, and resonated with the community, the Ashland Community Food Store on 3rd, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, the weather, recreation, and the schools. In fact, we both landed jobs in local schools the following fall. That was 1989, and the Viani family blended easily into the relaxed pace that defines our perception of Ashland. We have returned to all the places we lived abroad, and each visit was entirely different from the years living there. I think that is the defining merit of living in, rather than visiting, another country. Both result in valuable experiences, but only one allows you to watch a garden—or a child—blossom to fruition.

Alicia finished 2nd grade during our fifth and final year in Japan. The previous summer, Sooney attended the 3-week Oregon Writing Project in Ashland, OR, and resonated with the community, the Ashland Community Food Store on 3rd, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, the weather, recreation, and the schools. In fact, we both landed jobs in local schools the following fall. That was 1989, and the Viani family blended easily into the relaxed pace that defines our perception of Ashland. We have returned to all the places we lived abroad, and each visit was entirely different from the years living there. I think that is the defining merit of living in, rather than visiting, another country. Both result in valuable experiences, but only one allows you to watch a garden—or a child—blossom to fruition.

Related posts:

Balikpapan notes Part 1: viani.us/2013/11/kitchen-ching

Balikpapan notes Part 2: viani.us/2013/12/trail