Submitted to Sun Magazine: Readers Write on “Guns” (for July, 2007, issue)

“Ping.” The .22 had killed again. I drove in another cartridge, clicked on the rifle’s safety catch, and resumed my walk.

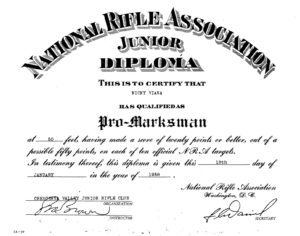

Shooting was a weekly activity for years when I was a kid. Every Saturday morning, a neighbor and I would somehow end up at the Glendale Police shooting range as members of the National Rifle Association’s junior marksmanship program. Shooting at the paper targets was a natural outlet for an 10-year-old obsessed with “playing war,” a favorite pastime of my friends in the early fifties. We’d drape oversized war surplus equipment over our scrawny bodies and think we were hot stuff. Truth be told, it sure beat the piano lessons I had successfully sabotaged the previous spring by freezing during my first recital.

The Junior Rifle Program was well organized and consisted of 7 competency levels, each progressively more difficult and rewarded with embroidered brassards (a fancy name for patches) and medals as incentives. The entry level consisted of passing a safety check and demonstrating proper behavior on the firing line. There were spaces for about thirty shooters, and many owned specialized target rifles characterized by heavy barrels, customized stocks, and an intricate leather sling that securely attached the shooter to the rifle.

The Junior Rifle Program was well organized and consisted of 7 competency levels, each progressively more difficult and rewarded with embroidered brassards (a fancy name for patches) and medals as incentives. The entry level consisted of passing a safety check and demonstrating proper behavior on the firing line. There were spaces for about thirty shooters, and many owned specialized target rifles characterized by heavy barrels, customized stocks, and an intricate leather sling that securely attached the shooter to the rifle.

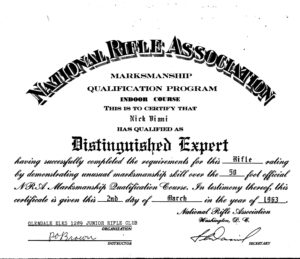

A couple days before my 18th birthday I attained the highest award for marksmanship—the Distinguished Expert award. It took over a year to collect the required 40 successful “targets,” ten each in the four shooting positions: prone, sitting, kneeling, and off-hand (standing). We fired 2 shots at each of the bull’s-eyes and, in order to count a target, all 5 bull’s-eyes required a score of 16 or better when firing in the kneeling and standing position, and 18 when shooting from the sitting and prone positions. It took nearly a year of Saturdays to complete the highly coveted “DX” award—particularly challenging during baseball season—and I recall how proud I was for remaining focused on mastering that difficult level.

A couple days before my 18th birthday I attained the highest award for marksmanship—the Distinguished Expert award. It took over a year to collect the required 40 successful “targets,” ten each in the four shooting positions: prone, sitting, kneeling, and off-hand (standing). We fired 2 shots at each of the bull’s-eyes and, in order to count a target, all 5 bull’s-eyes required a score of 16 or better when firing in the kneeling and standing position, and 18 when shooting from the sitting and prone positions. It took nearly a year of Saturdays to complete the highly coveted “DX” award—particularly challenging during baseball season—and I recall how proud I was for remaining focused on mastering that difficult level.

Some time later—I don’t recall when—my dad and I visited a friend of his living in the high desert north of Los Angeles. I still have a photograph of my dad and me, side by side, me holding my rifle held as I would later hold our daughter—across my chest.

It’s really sketchy, but for some reason I ditched the adults (my dad wasn’t a shooter) and entertained myself wandering the expansive property, shooting up a storm. I knew I wasn’t putting anyone in danger because I proudly wore the “Safe Hunters” badge on my shooting jacket. A .22 bullet is still lethal a mile away, and my technique was unquestionable. I was trained. And off I went, shooting every darn critter I could find.

As the day progressed, shadows got longer, and I returned home, probably to eat. When asked how’d the “plinkin'” gone, I proudly responded how I’d shot upwards to 20 birds. Our host looked at me curiously and then asked, “Why’d you go and do a damn fool thing like that?”

I’ve tried unsuccessfully to remember my father’s role in all this—he was a private kind of guy, and we didn’t talk that much. I do, however, remember the incomprehension in our host’s voice. That, and selling my rifle soon after.